By Oak Park resident, Peter Werbe

I never wanted to live in a suburb. I was born and raised in Detroit, attended its schools and, although I went away to college for a period, I finished my studies at Wayne State University. My wife and I happily moved into the area surrounding its campus with an appreciation of the student activism and exciting cultural scene of the time.

The suburbs always represented to me the worst about America. Culturally sterile, ticky-tacky houses, the artificiality of shopping malls, and – let’s be frank – where white people often moved so as not to live

close to minorities.

Each fall in the Detroit pubic schools I attended, the social studies department would sponsor a model  United Nations, a miniature replica of the actual session occurring simultaneously at the UN headquarters in New York City. The flags of the many nations were flown, and students would be chosen to represent ambassadors from the world’s different countries, sometimes even donning the garb of their nation of origin.

United Nations, a miniature replica of the actual session occurring simultaneously at the UN headquarters in New York City. The flags of the many nations were flown, and students would be chosen to represent ambassadors from the world’s different countries, sometimes even donning the garb of their nation of origin.

Duly assembled, we would hold a pretend UN session where we worked on solving the world’s problems. I was always fascinated by the diversity of cultures even in this small representation of them.

By the 1980s, Detroit proper was hollowed out by de-industrialization driven by corporate search for cheap labor and white flight enabled by bank loans for massive suburban home construction and individual mortgages. Beginning in the 1950s, the government generously financed freeways to provide mobility to a new generation of segregated suburbs.

With its tax base eroded and good jobs having disappeared, Detroit’s remaining residents (mostly African Americans) who couldn’t afford to leave the city or were refused entry to suburbs like Dearborn, faced deteriorating urban conditions accompanied by a rise in crime.

After a third burglary at our house in a year, my wife and I decided that, since we had the white privilege of residential mobility, we had to move to a safe housing situation particularly since I often worked overnight shifts as a WRIF-FM radio DJ. The prospect of moving to the ‘burbs, as we called them, was extremely depressing as we viewed them as representing everything that was wrong with our country — particularly racism, but also consumerism, Ozzie and Harriet-style families, and the epitome of the car culture.

As it turned out, we never looked anywhere other than Oak Park, since we were unintentionally aided in narrowing our search by someone who reacted negatively when we mentioned the city to which we eventually moved. We were told that anywhere south of I-696 “was still Detroit.” We knew then where we were moving. Up until the 1950s, Oak Park was predominantly a white, Catholic enclave. But, with the post-World War II housing boom, builders filled in the city’s wetlands and constructed affordable homes. Our new next-door neighbors on the East Side of Oak Park, who had been residents of the city since the late 1940s, said that before the construction frenzy of the early 1950s, they could see the traffic on Greenfield two miles away across what was then designated as “swamps.”

Jewish families from Detroit’s Northwest Side began migrating to the new and sometimes uniquely designed homes, such as the Lustron prefab steel homes on Oneida. And then the echoes of my school day’s model UN began to emerge in Oak Park. African Americans followed the Jewish population, then Chaldeans, Asians, Russians and Muslims making the word, diverse, a thriving reality. And, thrown into the mix are those of us from a European heritage who appreciate a city that isn’t of homogenous ancestry.

Oak Park’s disparate ethnic groups maintain a distinct identity around their own cultural markers and, to some extent, neighborhoods, but we all come together around the city’s institutions—its government, public facilities, and festivals.

This diversity is a source of pride to most Oak Parkers. Living in a city with good leadership, low crime, and excellent city services is reason enough to want to be within our borders. But, what makes our city special is that we look and act like a world of harmony— something desperately needed in these times.

I’ve accumulated a particularly excessive number having worked in radio for years where they were issued to the staff with regularity. Every so often, I take the ones that I figure I’ll never wear again or have gotten a little too snug (ahem!) to the Salvation Army store on 4th Street in Royal Oak.

I’ve accumulated a particularly excessive number having worked in radio for years where they were issued to the staff with regularity. Every so often, I take the ones that I figure I’ll never wear again or have gotten a little too snug (ahem!) to the Salvation Army store on 4th Street in Royal Oak.

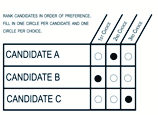

the last general election, a voter may have marked their ballot 1) Clinton, 2) Stein, 3) Johnson. If any candidate gets a simple majority, they win. If nobody gets at least 50 per cent, then the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and if that candidate is your first choice then the second choice on your ballot is counted instead. The process continues until finally one candidate emerges with majority support of the electorate.

the last general election, a voter may have marked their ballot 1) Clinton, 2) Stein, 3) Johnson. If any candidate gets a simple majority, they win. If nobody gets at least 50 per cent, then the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and if that candidate is your first choice then the second choice on your ballot is counted instead. The process continues until finally one candidate emerges with majority support of the electorate.

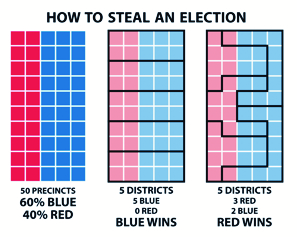

dedicated to democracy and America. Names like “Fair Districts Mass” and “Protect Your Vote” and “The Center for a Better New Jersey.” But a deep-dive investigation by ProPublica (an independent, nonprofit newsroom that produces investigative journalism with moral force.) found that while these groups purport to help represent voters in their communities, their main interest is gaining a political advantage in the fight over redistricting. Powerful players are turning to increasingly sophisticated tools and techniques to “game” the redistricting process, while voters are almost all blind to their shenanigans, and ultimately losing.

dedicated to democracy and America. Names like “Fair Districts Mass” and “Protect Your Vote” and “The Center for a Better New Jersey.” But a deep-dive investigation by ProPublica (an independent, nonprofit newsroom that produces investigative journalism with moral force.) found that while these groups purport to help represent voters in their communities, their main interest is gaining a political advantage in the fight over redistricting. Powerful players are turning to increasingly sophisticated tools and techniques to “game” the redistricting process, while voters are almost all blind to their shenanigans, and ultimately losing. two parties manipulate our election maps in 2020, when the next census is conduct-ed. Both parties are preparing to continue the tradition of partisan gerrymandering and have very distinct and aggressive strategies in place to secure voting districts: the Republicans are preparing a project called REDMAP 2020 and the Democrats are preparing their own project named ADVANTAGE 2020.

two parties manipulate our election maps in 2020, when the next census is conduct-ed. Both parties are preparing to continue the tradition of partisan gerrymandering and have very distinct and aggressive strategies in place to secure voting districts: the Republicans are preparing a project called REDMAP 2020 and the Democrats are preparing their own project named ADVANTAGE 2020.

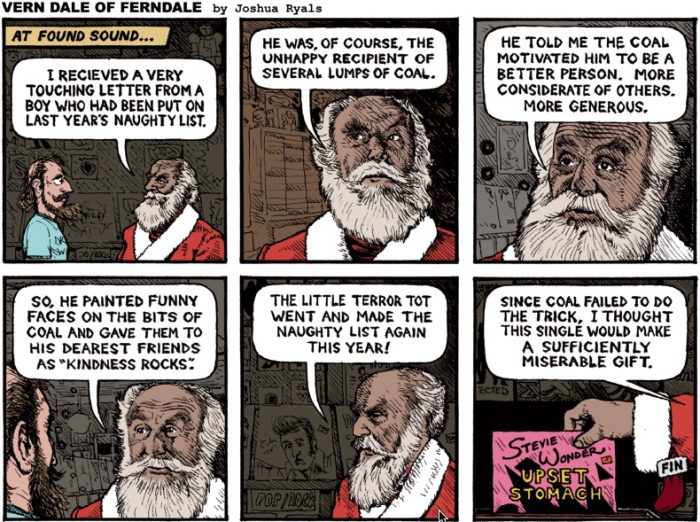

Sarah Lynn Fox liked the signs she was seeing, too. She and her husband, Brian Stawowy, noticed them as they walked their dogs around the neighborhood. Sarah said, “It made me feel so great to see all the signs…proud to live in Ferndale.”

Sarah Lynn Fox liked the signs she was seeing, too. She and her husband, Brian Stawowy, noticed them as they walked their dogs around the neighborhood. Sarah said, “It made me feel so great to see all the signs…proud to live in Ferndale.” town.” They both mention “admiring their neighbors’ houses, the front yard gardens”. Brian said the best part was “us working together and meeting our neighbors face-to-face.” They loved the chance to get to know more about their adopted home town. People were friendly, inviting them in and sharing their Ferndale knowledge with them.

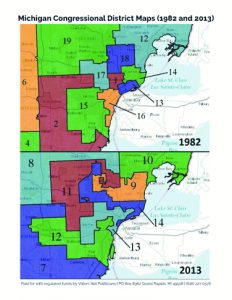

town.” They both mention “admiring their neighbors’ houses, the front yard gardens”. Brian said the best part was “us working together and meeting our neighbors face-to-face.” They loved the chance to get to know more about their adopted home town. People were friendly, inviting them in and sharing their Ferndale knowledge with them. Along with the signs, Fox and Stawowy are circulating petitions to support “Voters, Not Politicians,” a ballot proposal to end gerrymandering in Michigan. It’s an important, non-partisan issue. “You have to start some-where,” says Fox. “We can no longer make excuses to not get involved.”

Along with the signs, Fox and Stawowy are circulating petitions to support “Voters, Not Politicians,” a ballot proposal to end gerrymandering in Michigan. It’s an important, non-partisan issue. “You have to start some-where,” says Fox. “We can no longer make excuses to not get involved.”

only metal that can go in the carts are cans and empty aerosol cans,” Farris says. “These, along with Styrofoam and plastic bags can be brought to the SOCRRA drop off center for recycling.”

only metal that can go in the carts are cans and empty aerosol cans,” Farris says. “These, along with Styrofoam and plastic bags can be brought to the SOCRRA drop off center for recycling.”