Story by Jeff Lilly

THE PACE OF PROGRESS IS OFTEN SLOW AND HALTING. Sometimes we even take a step or two backwards. But, as Martin Luther King Jr. once observed, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

Charles Alexander, columnist for Between the Lines, has watched a lot of that arc. “In 1956, my senior year at Cass Technical High School, when I came out…” He pauses. “We were considered perverts, queers… there were no protections at all. Everyone was against us. The possibility of something like same sex equality was beyond belief, as were openly gay publications and organizations. None of this was in any way considered possible. If someone would have told me then (where we are in 2015,) I would have said they were crazy.”

The fight isn’t over yet. But how did we get to where we are today, to this crazy, wonderful world where loving couples of all descriptions can now freely marry? How did we build this lovely, inclusive city where people can feel free to be themselves?

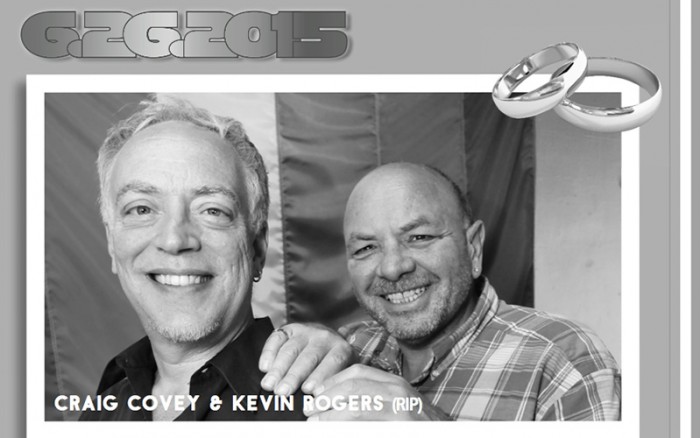

It started with a Supreme Court case that would seem ridiculous today. 1958’s One, Inc. v. Oleson was the first Supreme Court case mentioning gay issues. The ruling was that “speech in favor of homosexuals” was not considered obscene. A small enough start, but now at least it could be talked about. Former Ferndale mayor Craig Covey remembers, “Growing up gay or lesbian prior to (the 1970s) meant keeping everything very much under wraps. The worst fears of gay people besides getting beat up were being arrested by the police for simply being gay. When I was 24 and still living in Columbus, I had my cat run over and killed by homophobic neighbors and later my lover and I had our house set on fire by them. The police response to us was a suggestion that we move.”

It started with a Supreme Court case that would seem ridiculous today. 1958’s One, Inc. v. Oleson was the first Supreme Court case mentioning gay issues. The ruling was that “speech in favor of homosexuals” was not considered obscene. A small enough start, but now at least it could be talked about. Former Ferndale mayor Craig Covey remembers, “Growing up gay or lesbian prior to (the 1970s) meant keeping everything very much under wraps. The worst fears of gay people besides getting beat up were being arrested by the police for simply being gay. When I was 24 and still living in Columbus, I had my cat run over and killed by homophobic neighbors and later my lover and I had our house set on fire by them. The police response to us was a suggestion that we move.”

It was the bravery of early gay activists in the face of this onslaught that began to plant the seeds for social revolution. “I did hundreds of speaking engagements to thousands of people in the 1970s and ‘80s and gay activists did the same all over America.” Covey recalls. “That is how we got started on changing society.”

The first recorded gay activist group in Michigan was the Detroit Gay Liberation Movement, founded by Jim Toy in 1970. Progress was slow. A number of non-discrimination ordinances were passed in cities throughout Michigan, notably East Lansing in 1972, Ann Arbor in 1978, and Detroit in 1979.

Then disaster struck. “AIDS nearly wiped out the movement in the 1980s.” Covey says. “Many of our leaders were stricken and died.” But the survivors soldiered on.

Ferndale was just another Motor City bedroom community then, but LGBT people began to notice it. “At that time, Royal Oak was the place to be,” recalls Ann Heler, now director of FernCare. “But the cost of housing there had gone way up. So how could you stay near Royal Oak and still afford a home?”

Ferndale had a great supply of solidly-built, appealing houses that only needed a little TLC. It had a downtown crying for redevelopment. It was the perfect fit.

Nearby, in Palmer Park, Jeffrey Montgomery started the Triangle Foundation (now Equality Michigan) in 1991, out of the remnants of the Michigan Organization for Human Rights (MOHR.) Ferndale, following the leads of other cities, put a human rights ordinance on the ballot that same year.

Attorney and former judge Rudy Serra put together this first ordinance, designed to offer protections against employment and housing discrimination. He spent hundreds of hours in research. “I read every U.S. case dealing with a local civil rights enactment in existence.” He says. He then took to the streets to help gather signatures to put it on the ballot. “During the petition phase, almost no one refused to sign. There was no organized opposition at all until city council members… started the usual anti-gay scare campaign.” Although it contained language protecting against discrimination based on race, gender, disability, or sexual orientation, it was negatively portrayed simply as a “gay rights ordinance.” This misrep- resentation, combined with outside money from anti-gay groups and zero support from any elected officials or businesses, sent the measure to a heavy two-to-one defeat.

Attorney and former judge Rudy Serra put together this first ordinance, designed to offer protections against employment and housing discrimination. He spent hundreds of hours in research. “I read every U.S. case dealing with a local civil rights enactment in existence.” He says. He then took to the streets to help gather signatures to put it on the ballot. “During the petition phase, almost no one refused to sign. There was no organized opposition at all until city council members… started the usual anti-gay scare campaign.” Although it contained language protecting against discrimination based on race, gender, disability, or sexual orientation, it was negatively portrayed simply as a “gay rights ordinance.” This misrep- resentation, combined with outside money from anti-gay groups and zero support from any elected officials or businesses, sent the measure to a heavy two-to-one defeat.

In 1996, Ferndale’s LGBT community decided to step out a little with the foundation of FANs, or Friends and Neighbors. Started by Kevin Rogers, Robert Lalickie, and Mi others, it “didn’t start off as a political organization.” Ann Heler explains. “It was just gays and lesbians living inFerndale, saying hello.” FANs members volunteered locally, joined committees, and tried to be visible. “The idea was to get people used to the idea… of us.” Heler says. It was FANs that organized the first Pub Crawl in 1997 (now run by the Michigan AIDS Coalition), a major annual event that’s raised over $150,000 for charity.

But the homophobic elements in Ferndale and elsewhere were pushing back. A number of states enacted laws specifically banning gay marriage in the mid-‘90s. Michigan’s legislature overwhelmingly passed such a law in 1996, the same year the execrable Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) was enacted by Congress on the federal level. DOMA defined marriage as “between one man and one woman” and allowed states to not recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states. In Ferndale, meanwhile, a rash of anti-gay hate crimes erupted, coming to a peak in 1997.

“We looked at each other and said, ‘This isn’t right.’” Heler recalls. “You live in the neighborhood, you own a home, everybody should be safe.” So they formed the Police Positive committee, which Heler chaired. She called Ferndale Police Chief Sullivan, who met with members of FANs and the Triangle Foundation. Chief Sullivan’s response was immediate and unequivocal: “Criminal behavior of any kind has no place in Ferndale, period. It will not be condoned, and it will not be ignored.” Haters would still hate, but the police were firmly on the side of the local LGBT community.

“We looked at each other and said, ‘This isn’t right.’” Heler recalls. “You live in the neighborhood, you own a home, everybody should be safe.” So they formed the Police Positive committee, which Heler chaired. She called Ferndale Police Chief Sullivan, who met with members of FANs and the Triangle Foundation. Chief Sullivan’s response was immediate and unequivocal: “Criminal behavior of any kind has no place in Ferndale, period. It will not be condoned, and it will not be ignored.” Haters would still hate, but the police were firmly on the side of the local LGBT community.

1999 in Ferndale saw a second attempt at a human rights ordinance, this one organized by a blue- ribbon committee formed by Mayor Chuck Goedert. It was adopted by the city council and passed, but the victory was short-lived. A petition drive landed it back on the ballot in 2000 and it was overturned by popular vote. The final margin was agonizingly close: 51% to 49%. On that election night, Ferndale made national news when then-Councilman Craig Covey called the religious right a “vampire that needs a stake driven through its heart.” Gary Glenn (now representing District 98 in the Michigan House) came to a council meeting, and asked that Covey be arrested for that statement as a hate crime. He wasn’t. Statewide in 2004, Michigan voters passed Proposal 04-2, amending Michigan’s constitution to ban same-sex marriage. Over 58% voted yes. The tide was turning elsewhere, however. On May 17, 2004, Massachusetts became the first state to legalize same-sex marriage.

In 2006, prompted by local transgender leaders, a third effort to pass a human rights ordinance in Ferndale was once more undertaken, only to be dismayed when trans people were at first left out of the proposed ordinance. It was feared that including transsexuals might lead to the proposal being voted down a third time, and thus possibly killing it for good. However, Ann Arbor had amended their ordinance in 1999 and East Lansing in 2005 to include transgender people, and Grand Rapids (in 1994) and Ypsilanti (in 1997) had passed their ordinances including them right off the bat, so precedent existed. In the end, Ferndale’s ordinance was reworded to include transsexuals, and it passed easily, by a two to one margin. Ferndale would not only be welcoming to everyone, but everyone’s civil rights would be protected under the law.

What had changed? Straight folks were increasingly understanding that “(We’re) like everyone else, sharing common values, just different in one little way.” Heler muses. The increasing visibility of LGBT people in communities across the nation, the progressively less- stereotyped portrayals in the media of LGBT relationships and family life, the growing realization among the straight majority that the apocalyptic, society-destroying predictions of anti-gay forces were complete bunk, and, most importantly, the raising of a new generation who have lived, worked, and went to school with people who were unapologetically out of the closet have also played their parts. The courage of the early activists, risking reputation and limb to come out to a hostile world, was finally bearing fruit.

In November of 2007, a quarter-century after having his home be the target of attempted arson by bigots, Craig Covey was elected mayor of Ferndale, the first openly-gay elected mayor in Michigan.

In November of 2007, a quarter-century after having his home be the target of attempted arson by bigots, Craig Covey was elected mayor of Ferndale, the first openly-gay elected mayor in Michigan.

Nationally, despite continuing legal roadblocks, the momentum toward equality was unstoppable. In May of 2012, President Barack Obama openly voiced his support for same-sex marriage. In November of that year, voters in Maryland, Washington, and Maine legalized same-sex marriage, the first time this had been accomplished by popular vote instead of via court decision.

The news grew ever brighter. 2013 saw the U.S. Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision, rule DOMA unconstitutional (United States v. Windsor.) That same year, the court also decided (in Hollingsworth v. Perry) to overturn California’s Proposition 8, making same-sex marriage legal in California. Finally, June 26, 2015 came, and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on Obergefell v. Hodges, overturning bans in the last twelve states (including Michigan) where same-sex marriage was either illegal or partly restricted.

Work remains to be done. Civil rights protections for LGBT people at the federal level are spotty and incomplete. While some laws have been enacted, mostly regarding protections for federal workers, LGBT people are still not included as a class in national civil rights law.

Also, in Michigan, as Rudy Serra points out, “There are still sodomy and gross indecency laws.” Breaking these laws is a felony. “Criminal statutes overrule civil law. Accordingly, you can now legally marry your same sex spouse in Michigan and still get charged with a felony for having sex in the privacy of your home. This is an important remaining legal oppression of LGBT people in Michigan, (and) Michigan stands in open defiance of the U.S. Constitution.”

But for others, the writing is on the wall. “I honestly believe the movement is 98 per cent over,” says Covey, “because we have gotten rid of (many of the bad) laws, the ban on serving in the military, and now (we have) gay marriage. But truthfully, it was a whole lot of people working hard for 50 years that made all this happen.”

The arc continues, into the future.

“I want to recognize the Millenials.” Covey says. “I noticed their embrace of diversity over the past 15 years as I spoke on college campuses, and knew that it was just a matter of time…the millennials and the ones (who follow) are the generations that once and for all will get rid of racism and homophobia. I am so glad that I get to live to see it happen.”

Not everyone did live to see it happen. Many were killed by hate or snatched away by AIDS. Some just ran out of time, growing up and growing old in a world where they always had to hide, to suppress who they were out of fear of rejection, violence, or worse.

But we’re quickly heading on to a future where being gay or straight will be no more worthy of comment than having blue eyes or brown. Hopefully, when we get there, we’ll all be defined not by who we prefer to sleep with, not by our color or creed, not by the circumstances we were born into and the limitations imposed by society… but simply, and finally, by who we really are.

This led to a couple of cases where persons destroyed a rivals’s marriage by digging through their family history and finding that they or their wife had a great-grandfather, for example, who was not white. The law often made it so the couple had no choice but to divorce. It was especially bad in states like Arizona, where the laws, as written, kept anyone of mixed race from marrying anyone, even another person of mixed race!

This led to a couple of cases where persons destroyed a rivals’s marriage by digging through their family history and finding that they or their wife had a great-grandfather, for example, who was not white. The law often made it so the couple had no choice but to divorce. It was especially bad in states like Arizona, where the laws, as written, kept anyone of mixed race from marrying anyone, even another person of mixed race!